Brazilian indigenous languages

Threats to trunks and families of indigenous language and their speaker numbers

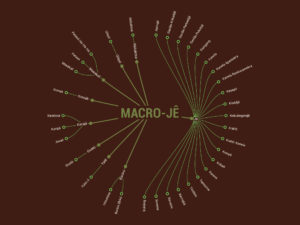

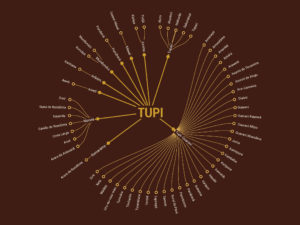

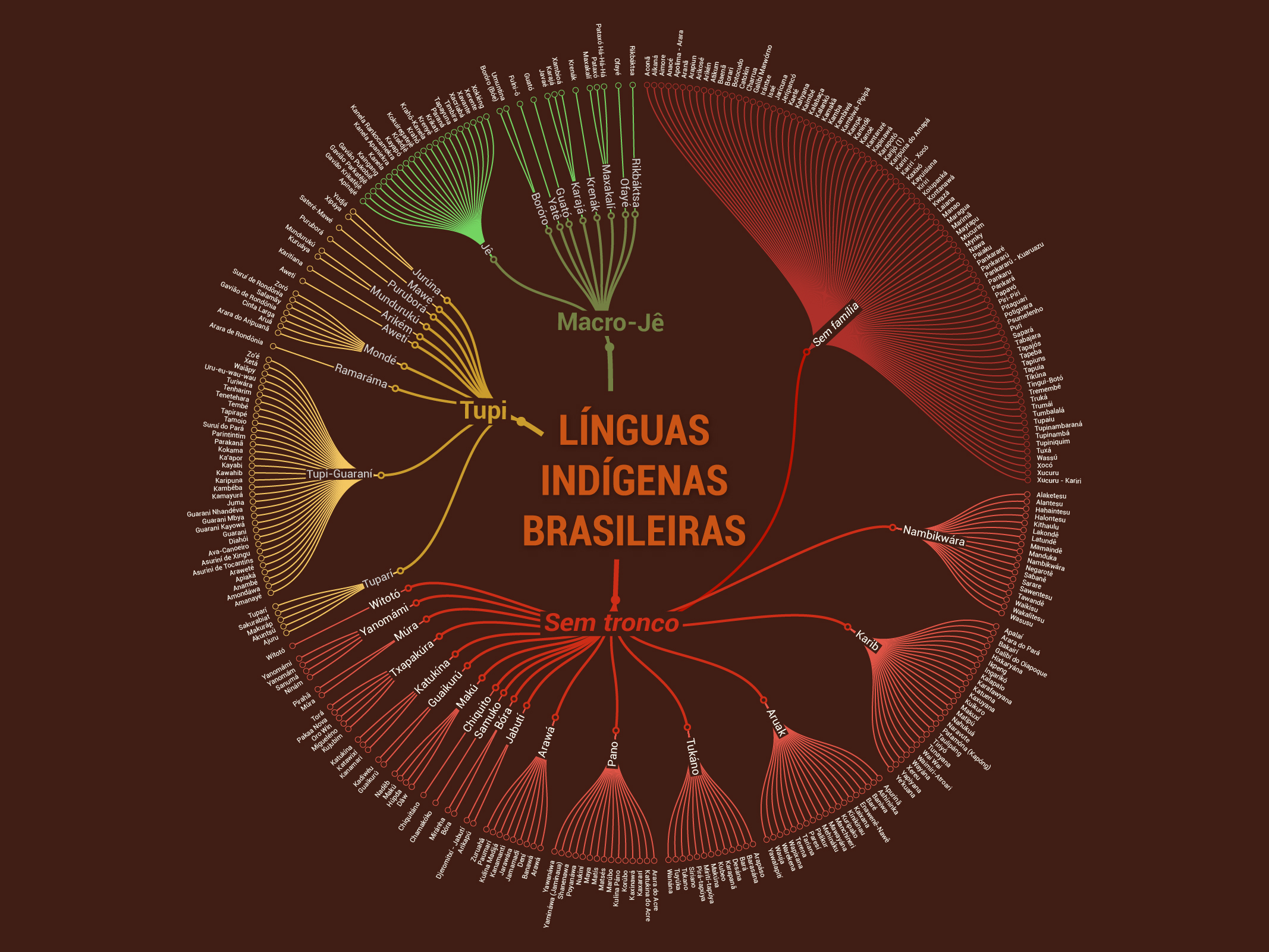

According to special surveys conducted by IBGE and Socio-environmental Institute (ISA), the number of speakers of several Brazilian indigenous languages is decreascing. The UNESCO Language Atlas (2006) revealed about 190 threatened. Only 305 were cataloged by IBGE (2010). Previously there were an average of 3,000 languages from just two main trunks: Macro-Jê and Tupi.

For a better understanding of the project I will briefly explain an important part of the linguistic structure. A trunk is an older language that is no longer spoken but structured many others, for example Latin. There’s a small degree of similarity between the languages that came from the same trunk, different from the family. The family would be like Portuguese and Spanish: many words are similar and the relation is clear.

In 1997 a professor called Ayrton Dall’Igna Rodrigues conducted a research for ISA, gathering information on Brazilian indigenous language families and trunks and cataloged them in his book: Brazilian Languages - for knowledge of indigenous languages. This work still the most cited among cataloging and eventual research like LALI (Laboratory of Indigenous Languages), of UFMG, one of the largest research centers on the subject that has not been updated since 2013.

Creation process

Project data were transcribed directly from IBGE research and confirmed with the UNESCO language atlas. Therefore a spreadsheet was made only for the project and with information from 2010, due to lack of new data.

I gathered 304 languages separated by the categories: Tupi, Macro-Jê, no trunk and no trunk / no family. This division gave some clarity for repeated cases and separation by hierarchies. Starting from the largest trunk to the smallest, I found that not all languages without a trunk, for example, have a low index of speakers. The circular dendrogram was chosen for its hierarchical character. The relation trunk > family > language was important to highlight. However, the draft reversed the order to trunk > language > family, which gives a more confusing character to visualization by repeating families (Ex.: Tupi-Guarani) in its posterior layer.

Methodology and Coding

Each color was defined for a trunk and its fading for families and languages, respectively. So the colors were yellow, green and red, on a brown background and the center was orange. The visualization was made to occupy an entire monitor screen, the letters of the final circle hardly appear. But right at the start, an instruction indicates that you can do two commands: ctrl + scroll to zoom in and ctrl + mouse to navigate. Then, when approaching and navigating, the visitor can hover over one of the languages, only in this situation can be seen the number of speakers and a color indicating their extinction scale. Red, yellow and green are the three colors that subdivide the letters of the mouseover stripes.

The visitor can also click on a trunk or a family, allowing an animation to unfold. Then the family name or trunk goes to the center of the screen, removing the others, and their languages spread around, allowing for closer proximity. To return to the main screen, just click outside. Attention, the click feature does not work if the user is pressing the ctrl button, which seves to zoom in or out.

A question mark has been added at the bottom left of the screen. Leading to a brief legend about the structure of the hierarchy, why the visualization is distributed as it is.

Conclusion

With the need for a less tabular approach, I sought to perform a simplified data visualization by crossing data from UNESCO, IBGE, LALI and ISA. Due to difficulty in finding updates, I chose to change the focus on extintion. I believe it was importante to carry out this work for the indigenous approach, an point that is gradually being more discussed today.

Visit labvis.eba.ufrj.br for more.